Macular Degeneration

Macular degeneration is a common eye condition affecting millions of people worldwide, particularly those over fifty. At Center for Sight, our physicians have the experience and knowledge necessary to diagnose and treat macular degeneration and prevent vision loss.

What is Macular Degeneration?

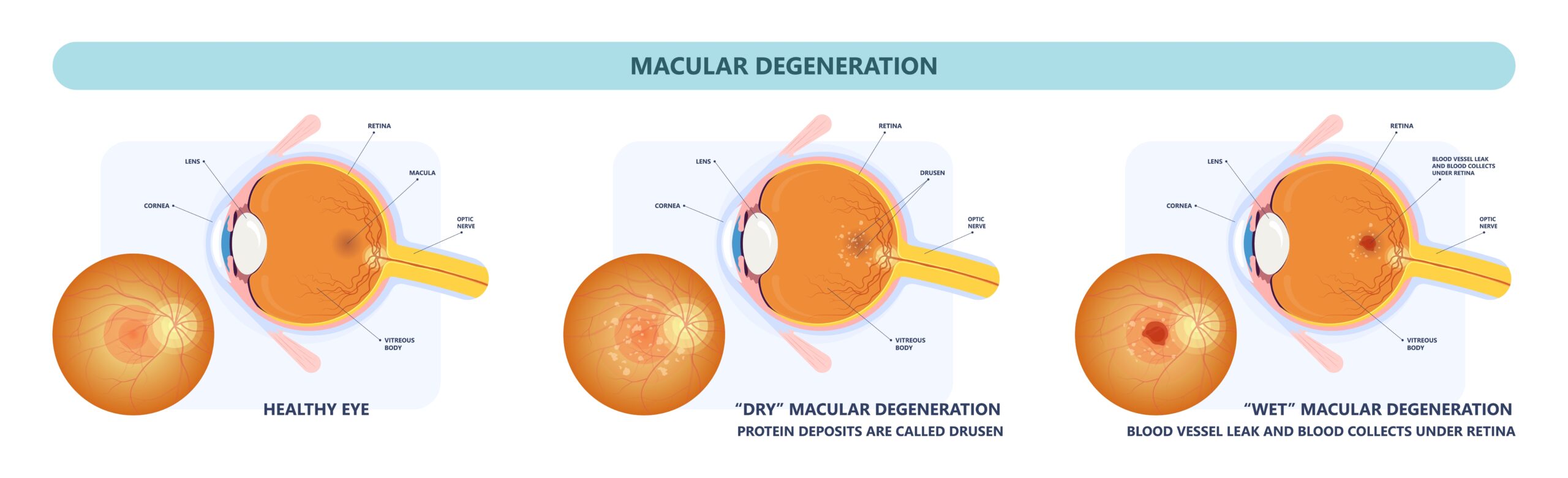

Macular degeneration, also known as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), is a degenerative eye condition that causes damage to the macula. The macula is a small but important part of the retina located in the back of the eye.

It is responsible for sharp, detailed, and central vision. When it is damaged, it can lead to severe vision loss or even blindness.

There are two types of macular degeneration: dry and wet. Dry macular degeneration is the most common type and occurs when the macula thins over time.

Wet macular degeneration is less common but more severe. It occurs when abnormal blood vessels grow in the back of the eye, leading to leakage, scarring, and potentially significant vision loss.

What are the Symptoms of Macular Degeneration?

The symptoms of macular degeneration may vary depending on the type and severity of the disease. However, the most common symptoms of macular degeneration include the following:

Who is At-Risk for Developing Macular Degeneration?

Certain factors may increase your risk of developing macular degeneration. One significant risk factor is age. Macular degeneration is more common in people over the age of fifty. The risk of developing macular degeneration may also be higher for those with a family history of the condition.

Smoking can also increase your risk of developing macular degeneration by two to four times. In addition, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and other cardiovascular diseases may increase the risk of macular degeneration.

It is important to note that anyone can develop macular degeneration without possessing any risk factors.

What Treatments Are Used for Macular Degeneration?

Unfortunately, there is currently no cure for macular degeneration. However, treatments are available to slow the condition’s progression and preserve vision.

At Center for Sight, our vitreo-retinal specialist offers a variety of treatments for macular degeneration.

Dry macular degeneration in its early stages is typically treated with nutritional therapy, which involves eating a nutritious diet rich in antioxidants to maintain the macula’s cells. Supplements containing larger doses of specific vitamins and minerals that may boost healthy pigments and strengthen cell structure are advised if the condition is more advanced but still dry.

Wet macular degeneration is commonly treated with anti-VEGF injections. Anti-VEGF injections block the growth of abnormal blood vessels in the eye. These injections are given directly into the eye by your vitreo-retina specialist.

Wet macular degeneration can also sometimes be treated with a specialized procedure during which a laser is used to cauterize leaking blood vessels to prevent them from causing further damage. This is done with the ultimate goal of slowing down the process of deterioration inside the eye.

The best treatment method for you based on the severity of your condition and other factors will be determined by your physician. If you are diagnosed with macular degeneration, it is important to visit your eye doctor regularly to receive timely treatment to avoid vision loss.

Are you experiencing vision changes or other symptoms of macular degeneration? Schedule an appointment at Center for Sight today!